A feathered past, and present: calling out bad birding behaviour

Authors: Jennifer Lavers and Alexander Bond

Late last year, Alex and I found ourselves hidden amongst the palm forest surrounding the Lord Howe Island Research Station. In between field work that involves catching shearwaters under the cover of darkness, we write. Our annual field season/writing retreat on this remote island is one of the few moments we have where the outside world fades away – no emails, no deadlines – and creativity flows. We brainstorm ideas, process data, spend time thinking, and seek out new collaborators who can help us address priorities. And of course, we write.

For a long while we’d reflected on the name of our main study species, the Flesh-footed Shearwater (Ardenna carneipes). We knew the origins of the name were problematic, with the birds’ pale feet being “flesh” coloured and the default assumption being that flesh equates with whiteness. With a series of recent, inspirational name changes leading to positive outcomes, we felt the time had come to revisit the name of our beloved shearwater.

So, in between catching shearwaters, we developed an outline for our paper, the focus of which would be to identify a suitable Indigenous name. But here was the issue: these migratory, trans-hemispheric birds simultaneously belong to no one and everyone. Which Indigenous communities should we approach, and ultimately, who would get to choose the name?

Alex and I are fortunate to undertake much of our science under the guidance of Indigenous Elders. Blending western and traditional knowledge presents an opportunity to reimagine how we protect and come to understand species, but there is also a cost. Many Indigenous communities are small, remote, poorly funded; these conditions are not conducive to freely assisting scientific endeavour, however simple the requests for engagement might seem.

With great care, we consulted with a handful of Indigenous communities in south-western Australia, where the bulk of the species breeds. With more than 800 Indigenous language groups in Australia alone (never mind Japan, New Zealand, Canada and the USA where the birds are also found), it was immediately apparent that identifying one, unifying Indigenous name was not only impossible, but a huge imposition on communities.

A. carneipes would be given a western name.

A lot of effort goes into finding the perfect name (ask any parent). Over many weeks, Alex and I weighed up the names on our list, and one by one, eliminated them. ‘Austral’ was too similar to nearly a dozen other species, ‘black’ was too generic, chocolate (or brown) only applies to adults with worn feathers. But the term ‘sable’ immediately stood out. Commonly used to refer to something having ‘dark brown or black colour’, sable is also a French term for sand. A. carneipes is an all-dark shearwater that nests in sandy substrate. Decision made.

Welcome to the world, Sable Shearwater.

In September 2024, we were excited to see our paper featuring the new name published online in Ibis (link here). We hoped the ornithology community would celebrate the change and recognise the important messages contained within the paper; even when well-intentioned, blending western and traditional knowledge can be difficult or even impossible, and we should tread lightly.

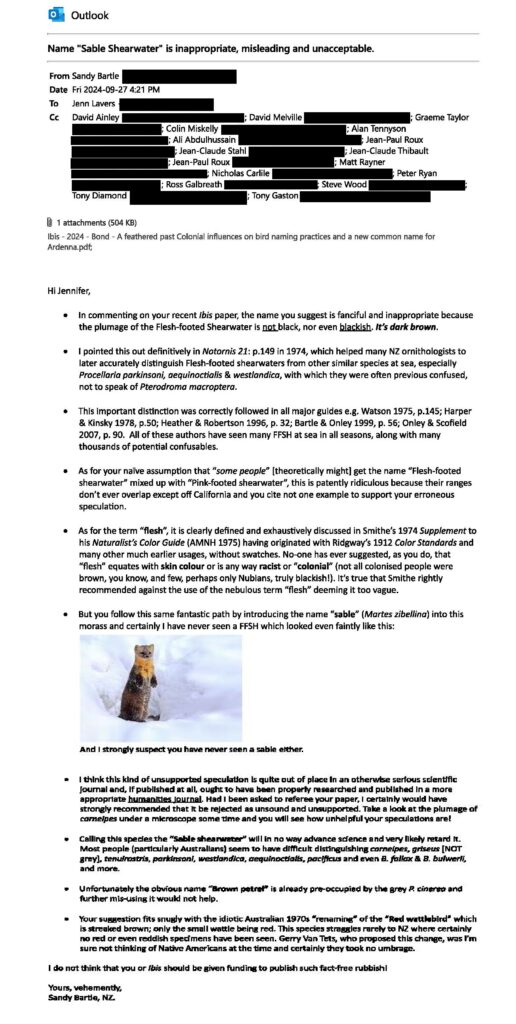

The feedback we received was immediate, and while much of it was positive, we were shocked to see comments that were personal and overtly racist. The author of one particularly email chose to share his hateful comments with 16 of our colleagues, peers, and mentors (all of whom are male) who were cc’d into the email. Rather than shy away from this issue, we are choosing to address it head-on by sharing the email publicly, in its entirety.

We must all act with speed and determination to call out such inappropriate and offensive behaviour.

But Sandy’s email is just a symptom of a much broader issue. Within science, and in particular, birding communities bad behaviour is often repeatedly ignored, and as a result, these spaces are not safe for many, especially women, people of colour, and those who identify as LGBTQIA+ (long list of references below).

Don’t believe us? Here’s a recent example directly related to A. carneipes: as of 28 September, the BirdGuides birding page includes 53 comments from the birding “community” (the majority appear to be written by white men) that attack the contents of our paper, and unnecessarily criticise both authors. Only one person on the BirdGuides page called out the inappropriate and often racist comments stating “I don’t see why anyone would have a problem making birding more accessible. If we want to save nature we have to make it appealing to all and removing any hints of racism from species names is a great step in that direction and harms absolutely no-one”.

In subsequent days, one of the other recipients of Sandy’s email sent a reply to the group suggesting that while some of Sandy’s comments were out of line, we should disregard these bits and simply focus on his salient points. Sandy himself has also replied, stating he has “always been known for [his] intemperate remarks” while also arguing that the onus is on the rest of us to look past his aggressive comments and see the value in his original email. This is the definition of gaslighting, and it’s not okay. Sandy goes on to point out that one of our* key failures is that we did not consult the birding community when working to identify a new name for A. carneipes. This argument is moot – we again refer the reader to the 53 comments above, nearly all of which had racist undertones. Many members of the birding community are not ready to have a calm and reasonable discussion about naming issues.

Back over to you, community – your turn to do the work.

*and by “our” we mean Jenn. Throughout Sandy’s email it’s “she did this” or “Jenn did that” and “her paper”. Alex (the first author) is not mentioned once, anywhere.

For more than two decades, we have each worked to make science in general, and ornithology in particular, a more welcoming place to many – women, queer folks, Indigenous people, and others. And while things are improving compared to when we were both graduate students, there is clearly still a long way to go. Talking about, and sharing, messages like that from Sandy will shine a light on the toxic legacy of our profession – which is in need of some sunlight and disinfection.

References

Widespread use of non-disclosure agreements in Australia is ‘protecting serial predators’ (2022)

Birding in the UK: Where Are the People Like Me? (2020)

For the LGBTQ Community, Birding Can Be a Relief—and a Source of Anxiety (2018)

Bullying in Birding (Bird Forum 2021)

When students become class bullies, professors are among the victims (2010)

Guilty until proven innocent: social media and bird photography (2021)

Subscribe for updates

Keep up to date with what we’re working on! We’ll send you emails about the lists you opt in to, and you can unsubscribe at any time.